Report warns vulnerable people living in poor-quality homes at particular risk this winter

Newly-published research has highlighted the increased risk poor-quality housing has on those identified as being most at risk of COVID-19, such as the elderly and people with pre-existing healthcare conditions, especially in the event of a winter lockdown.

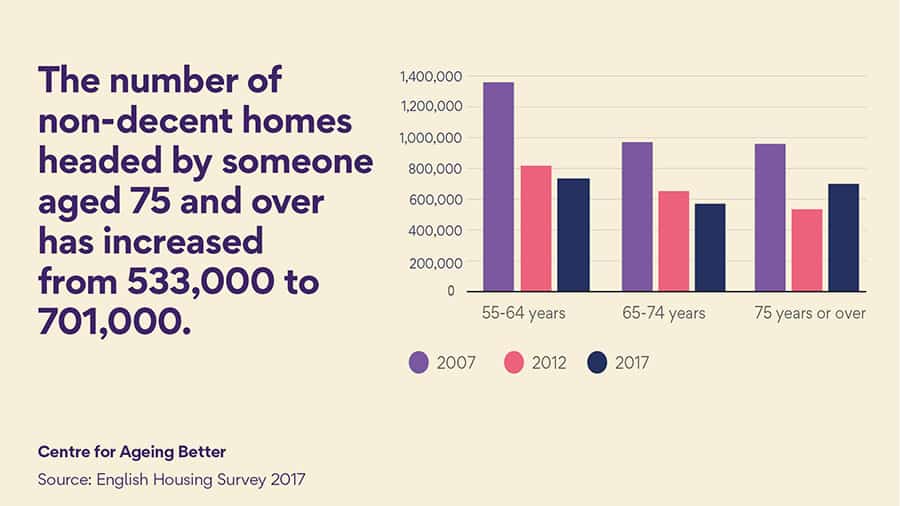

The joint report from The Centre for Ageing Better and The King’s Fund points to data suggesting 4.3 million homes in England are what the government defines as ‘non-decent,’ putting the health and wellbeing of their estimated 10 million inhabitants at risk.

According to the paper, people that have been identified as most at risk of COVID-19, including older people, those with pre-existing health conditions and Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority groups, are more likely to be living in non-decent homes, along with those on low incomes.

In particular, the study picks out excess cold and damp – two of the most common reasons homes are deemed non-decent – as being particularly dangerous to those vulnerable to the disease.

With cold housing already accounting for an approximate one in five excess deaths during winter, the Centre for Ageing Better notes that individuals required to spend more time in such conditions may contract and exacerbate several chronic health problems, including respiratory and cardiovascular conditions.

Holly Holder, Senior Evidence Manager at the Centre for Ageing Better, says: “Winter is always a worrying time for people living in poor-quality, cold and damp homes, particularly for those people who struggle to afford to heat them and keep them warm. This winter, millions could find the danger they face is even greater. Spending long periods of time in a cold, damp and unsafe home is bad for people’s health and could increase the risk of serious consequences if someone were to contract COVID-19.”

The report warns that the financial pressures stemming from COVID-19 may also make it harder for homeowners to make the changes needed to their homes, with approximately 2.5 million owner-occupied households failing to meet the standards (17 per cent of all owner-occupied homes). Those living in the private rented sector are also of concern as 25 per cent of these households are in a non-decent condition (1.1 million homes).

“The government urgently needs to reach out to these at-risk groups so any immediate interventions can be made to make homes warmer, free of damp and safer,” continues Holly.

“We also need government to address the crisis in the quality of housing and recognise the key role that housing plays in the health resilience of our communities.”

Alongside the healthcare pressures of remaining in non-decent homes, the organisations warn that a winter lockdown could also see increased fuel bills and exacerbate fuel poverty for those spending more time in their homes who may already be struggling to keep poorly insulated homes warm for longer periods.

Clair Thorstensen-Woll, Research Assistant at The King’s Fund, said: “We have not all experienced lockdown equally. Many vulnerable people have spent more time in homes that are unsuitable, cramped or physically unsafe; environments which place residents at higher risk of worse outcomes from COVID-19.

“The pandemic has shone a light on the mounting evidence that poor housing has a detrimental impact on people’s health. Tackling the problem will require better quality housing, improvements to the neighbourhoods around people’s homes and greater alignment of the housing, health and care sectors. The issue of poor housing and its impact on health should no longer be swept under the carpet.”

In response, the Centre for Ageing Better is calling on the government to make sure at-risk groups have the support they need now to make their homes warmer, free from damp & mould, as well as safer.

The charity says that for some, this means providing trusted information and advice to signpost them towards those who can help. For others, this will require more direct intervention, such as financial support.

Additionally, the charity advises the government to work with landlords to ensure that rental properties are safe.

Evidence presented in the report reinforces the cost-effective impacts of interventions to improve housing quality, both in and outside of the home. The study contends that every £1 spent on improving warmth in homes occupied by at-risk households can result in £4 of health benefits, while £1 spent on home improvement services to reduce falls could potentially lead to savings of £7.50 to the health and care sector.

Considering what needs to be addressed in the longer term to fix England’s housing, the Centre for Ageing Better urges the government to put housing at the heart of strategies to build the population’s health resilience in the wake of the pandemic.

The report also underlines the need for stronger relationships between housing and health and social care providers at a local level, warning that the important role housing plays in people’s health and wellbeing is too often overlooked.

It follows the government’s launch of a consultation to tackle the increasing shortfall in accessible housing, with considerations to change building regulations to prompt developers to build homes with future-proofing in mind.