Guest article: Are we applying too many technical access standards to buildings?

Do we have too many technical building standards? Are there gaps in those standards? Ron Koorm, Associate Consultant for the Centre for Accessible Environments (CAE), shares the benefit of his decades of expertise on the subject.

By Ron Koorm

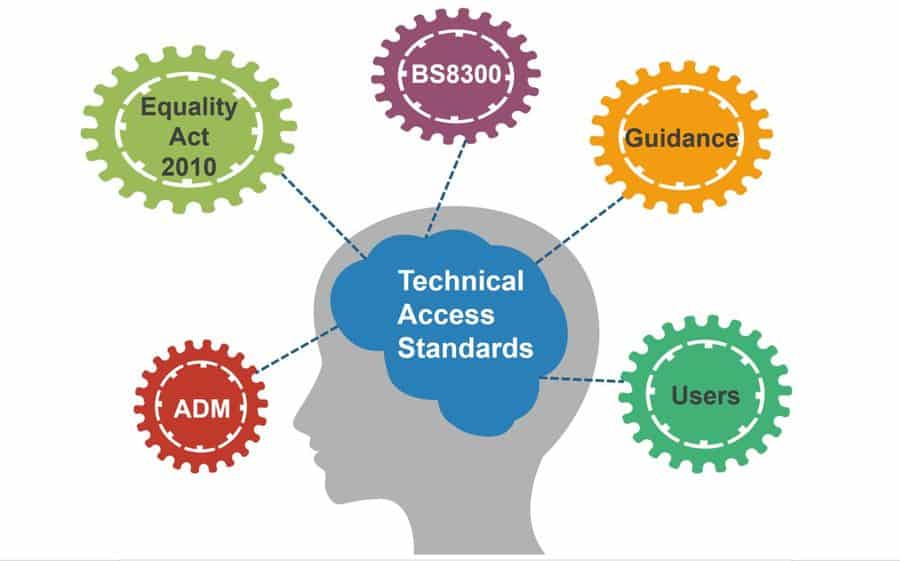

Designers, specifiers, access officers, consultants, and auditors are constantly trying to make the environment more inclusive. Whilst the backbone of this might be relevant legislation, i.e. The Equality Act 2010, in practice there are many technical standards that have evolved over the years, which need to be considered.

When advising clients about their properties and inclusion, professional and technical advisors have a duty of care to their principals, and unnecessary expenditure should be avoided. They need to be clear as to whether their recommendation is legislation-driven or best practice, or if it’s ‘nice to have’ or optional.

How many standards?

Technical standards rarely stand still. They are reviewed, scrutinised, amended, and updated. This happens quite a bit between Part ‘M’ and the Approved Document of the Building Regulations and Best Practice standard for accessible design, BS8300:2018. And yet, Approved Document ‘M’, isn’t even the law. It’s just a guide as to how one can comply with the law under part ‘M’.

There are many access technical standards: guidance documents, best practice standards, regulatory standards. From tactile paving to design of Changing Places toilets; from signage design guides to lighting design standards; wheelchair-design guides to accessible street furniture.

There is even a much-needed new draft standard due to be released for people who experience sensory and neurological processing difficulties. Perhaps, we need to consider the number of standards available.

Which takes precedence?

Are there too many standards? Do any of them overlap? If so, which takes precedence, and how much is influenced by case law on access claims?

Before professionals look in-depth at technical access standards, they should stand back and ask, ‘why are we applying this standard?’.

A good adviser should always bear in mind:

- The objective must always be to make a more inclusive environment without undue complexity in the process

- Whilst detail is important to access and inclusion, do not lose sight of the bigger picture. i.e. what is the driver for good access

- Interpretation of technical standards can vary between professionals, clients, lawyers, and building control

- If you deviate from a best practice standard reasons need to be justified and recorded (e.g. access statements)

- Changes to technical standards need to be justified, otherwise there can be confusion and mistakes

- Lessons need to learned. For example, a degree of ambiguity in parts of technical standards or specifications could lead to errors and misunderstandings by design and construction teams

- Maintenance of buildings goes hand-in-hand with the technical standards and becomes crucial in maintaining good access. It is often overlooked.

Gaps in standards

Why is someone able to design and build a new building with inaccessible signage? Building regulations only require very limited signage controls, such as for fire egress, and the wheelchair-accessible WC symbol sign.

Consider the BSI BS 8300-2:2018 in the employer’s requirements for hand-dryer maximum sound pressure level (SPL) noise in your washrooms. It simply says designers need to be aware that loud noise can be distressing to some people. My view of what is ‘loud’ noise, may not be the same as yours.

Design and Build

In design and build contracts, one should be careful to get the employer’s requirements correctly drafted. Otherwise, the contractor will interpret them in his own way.

We need a process of ongoing education in design teams, to ensure people have a good understanding of access standards and criteria. Design and build contractors, and tradespeople should be included in this process too.

Applying technical standards should always be put into the appropriate context, otherwise, you’ll end up with the wrong solution. Once we have most professionals onboard applying the existing standards on access, then we can concentrate on updating those and filling in the gaps.

User Engagement

Also, when standards are being formulated or reviewed it is prudent to engage with disabled people, professionals, and others for consultation.

This can include the use of focus groups to talk through changes, and ensure that barriers are removed from inclusion. This process should also form part of a key stage in the review of the draft document in order to consider the views of disabled people.

The Centre for Accessible Environments runs a variety of public training courses on access and inclusive design across the year which can be tailored and adapted to organisations’ objectives, and requirements, for up to 15 people.